Beyond Growth: Reining in the Tides of Capitalism

How governments and grassroots movements are implementing steady-state and degrowth strategies to counter capitalism's environmental and social costs.

Episode 33-2

7/3/2025

Having laid out the fundamentals of Steady State and Degrowth, Part II of this segment explores why critics of the capitalist system advocate that these approaches are necessary both to achieve a sustainable planet and improve quality of life for people. Jorden and Kimberly consider where we see evidence of governments and communities applying Steady State and Degrowth approaches, with the hope of countering the ills of a broken system.

Key Topics Jorden and Kimberly discuss include:

How Jorden missed the fact that there is a thriving degrowth community lurking in his own backyard

Why Congestion Charges promote sustainability without devolving into communism

How local movements—from community gardens to ecovillages—challenge the underlying principles of capitalism

Why the Fair Trade movement might be the best global-scale example of sustainability advocacy policy at work

How one international agreement managed to revitalize a dying elephant population

Recommended Resource

The Fair Trade Story video

The Global Ecovillage Network and a list of ecovillages

Steady State’s organization page and more about Steady State

The origins of Decroissance and more about Degrowth

Kimberly’s Substack newsletter post

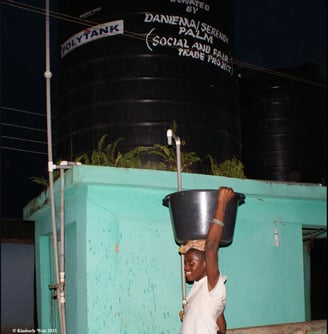

The Serendipalm Fair Trade cooperative funded this $86,000 water pump to provide clean water for the local village. A significant portion of the expense was due to the need to run miles of power lines to a village with no electricity.

Episode Transcript

KIMBERLY

Welcome to this episode of Sustainable Planet. I'm political scientist, Kimberly Weir, and my co -host is Jordan Dye, a guy who knows an awful lot about sustainability issues. Over the last few episodes, landfills, planned obsolescence, right to repair, and circular economy, we found that mountains of garbage are piling up, yet we face shortages of resources. So we need to move to a more sustainable way of production and consumption. So Jordan, is a steady state or even degrowth the answer?

JORDEN

No, it's not the answer. And that's all I have in my notes is a hard no. But I think just to kind of set where we're coming in on this issue for listeners, I actually think it's counterproductive to moving towards a sustainable world. I think that the degrowth conversation has. done more damage than it's helped and i i kimberly's already giving me a look and the reason i'm i'm confused by what you said you you think that it's done more harm than good to move in a sustainable direction i don't think that's actually what you meant is it oh it is it is okay because i have to spend time

KIMBERLY

i'm i'm confused by what you said you you think that it's done more harm than good to move in a sustainable direction i don't think that's actually what you meant is it oh

JORDEN

oh it is it is okay because i have to spend time So I find a lot of the degrowth has more come up in conversations for me with people who are against sustainable development and arguing, oh, you're just a degrowth or you guys want this. This is what you want. So I find that even I got to spend 30 minutes, an hour dealing with some people to get them that I'm not there. No, I don't think that's right. And then move them into an actual sustainable development conversation. I have talked about it more with people who are against it and use it to label the entire sustainable development and environmental movement than I've heard from actual like I do have friends, but degrowthers. That's why I think it's counterproductive is because it actually can be used to turn people away that I could get on the sustainable development side, but not on a degrowth or a steady state.

KIMBERLY

okay because

KIMBERLY

So people don't actually know what degrowth is, which is part of the problem then, because sustainability is not sustainability. And degrowth are not synonymous by any means. And steady state is a little bit closer to what it is that you're actually talking about.

JORDEN

Yes, I mean, I still disagree with steady state. And so I think that'll come out over this is that I don't think growth in and of itself is a bad thing. That's I think that's fundamentally where I come from on this issue is that growth itself isn't bad. How we grow, where we're growing and what we're doing, that's what can make it good or bad. And so, yes, steady state's much closer to, I think, like what. I do argue for, but I still see flaws more also just in the framing of it. Right. As saying, we're freezing it. We'll get into some of what I see are challenges with it later. But that's that's kind of where I'm coming from on this. And I will want to say up front, I actually agree with most of the the issue analysis. So like the what are the problems? I agree. Steady state and degrowthers. I agree with them on that. So there'll be a lot of agreement in this episode. It's when we move to the solution and what should we do and should degrowth or steady state be the solution that I start having my disagreements.

KIMBERLY

And so when we what we're really talking about with sustainable development, I mean, this obviously implies development still needs to happen, which does. Right. So most of the world's countries are underdeveloped. and need more development. But it has to be done in a sustainable way if we're going to be anywhere close to being able to maintain the planet without, you know, going to hell in a handbasket. The global north countries don't need more growth, but actually need to implement sustainable development strategies to retool non -sustainable practices. So we need to revitalize, rehabilitate, like replace outdated, inefficient infrastructure, those sorts of things. But the global south development shouldn't be based on what the goal would like. It's one of those don't do as we say, did do as we say. And so this is what brings about this development and all of this concern.

JORDEN

I want to pause here because actually I had a question here because I think this might be really useful to do now before we even get into the background on this. Because what do we mean by growth, I think is really important, because when we even their global North countries don't need more growth. There are ways that sentence could be said that I think I agree with. But then when I when I read it, even in our notes, I had to put a note of like, I don't think this is I don't know if we're actually saying the same thing, because I used an example here of go back to our sustainable fuel episode, right, where we were talking about some of the new fuels that are coming down the line. If a company in the global north developed a cheaper than any other fuel source that had zero emissions. And I mean, there's some that we're looking at that could be negative emissions. But let's just say we get that and they roll that out to the world. They have to build new manufacturing for it. They're selling it. That's going to drive growth. Right. But I think that we would all be very happy in the growth that that drove. So that's what I want to stop on that of like, because I don't think that saying that we don't need more. And we need the right kind of growth. But that's sustainable.

KIMBERLY

that's sustainable. What you just described is sustainable development. It is I mean, we need development in that direction in that it's very much about having cleaner energy sources that are not that are renewable, that that aren't, you know, fossil fuels wrecking our planet. And that's exactly that's exactly what that sort of growth actually means and implies. But that's not how the world typically looks at growth. It's almost invariably just GDP. What is the GDP of a country? What's the average income per person? And that's the beginning and the end of discussion. And for too long, that's all countries and corporations. and intergovernmental organizations have ever focused on. And very few have actually readjusted to consider, well, what are the social implications of these policies? What are the environmental implications of these policies?

JORDEN

No, I figured that that's what it was, but I thought it'd be good to stop at the start and say that when we're talking about negative growth or like growth negatively, what we're talking about is a single, a singular conception of growth and a focus on one aspect and can talk about good growth, like sustainable development, because as you said, it implies growth. So I just wanted to up front say that there can be growth that is still good. But to your point, it's not what is talked about or when you even talk about economic growth, what most people would mean.

KIMBERLY

Yes. And so the whole degrowth movement is very much came along with the whole environmental movement. And so the EPA was founded in 1970. Well, we also see Dr. Seuss publishing the Lorax, the Lorax, I speak for the trees, in 1971. And then the United Nations created the environmental program, the UN Environment Program. And that had its first convention in 1972. And then we see in 1973, really importantly, the sites, some people pronounce it CITES, but it's the Endangered Species Act. And it got huge international support. And it's actually one of the most prominent accomplishments ever to lay the foundation for African elephant conversation that really helped to repopulate elephant, the population in Southern Africa. conservation movement was really important and also helped to lay the foundation for some others that came along like the Montreal Protocol, which was in the 70s as well. And so the date's not surprising that this is when the degrowth movement comes around. In 1973, the seminal work was put out by an ecological environmentalist. And that was, Jordan, you mentioned ecological environmentalism. Sorry. ecological economics in the last episode and how you wish that that would just become the norm for economics instead of a subdivision. Herman Daly was the one who like was in the forefront of this. He's proposing at the time was proposing a steady state economy. And this was not degrowth, but this preceded this and it was no growth actually pushes. His approach was that it pushes to stabilize the population and the consumption. rather than pushing for constant growth, especially with the GDP at the cost of the environment. And so he's pushing here to try to retool how we look at economics and actually account for those externalities.

JORDEN

You know, I think it's great work. And yes, I like you mentioned, I do have a love for ecological economics. I think, though, already we're getting into a part of my problem with it is the first part of that is stabilized population and consumption. So let's put consumption for a side for a second. And because the other thing that was going on in this era was books like the population bomb and like a mass fear over what was either going to happen with stagnating population or too much population. Maybe I don't know how to say this other than just like I don't want any government anywhere getting in the business of deciding population levels. And so like if the system requires you to to create limits on that and to stop that, I think we get into really dangerous and dark territory.

KIMBERLY

China's one child growth. That's a really good example of what can really go wrong when you mess with nature.

JORDEN

Yeah, no. And but also just all the then the really weird and perverse impacts of that, you know, we know that it over selected to actually killing off female fetuses or young babies. When I was actually in China for a time, we were staying with a family where the daughter of the family, she talked to her brother every day. And I made a comment. I'm like, you have a brother like they're of the generation they would have been in one child. And she was like. no my my parents didn't want to get rid of me and were like happy to have a daughter so basically the family next to us we were raised as siblings because they had a son and we like almost shared as and like so i and i know that if like you know we talked to irman daily like no one wants to say that this is what we want on it but the second you say stabilized population we have to think past like what does that actually mean and so that's this is starting to get into like some of my problems with this is that i think that It has to go to a level of government control that A, we've never seen and B, I wouldn't be comfortable with.

KIMBERLY

Yeah. And there are things that go along with that. There are also pro natalist policies where there are governments that are pushing people to have more children and supports. And that's almost like subsidizing a dying industry. So, but there are absolutely good nationalistic reasons for this as well.

JORDEN

Yeah, no, and it's funny because I also like. I won't support pro natalist. I look at it like the best thing what the government should the government's role in family creation is to create a stable, stable environment. And then like you look in the global north, like you hit a certain cost of living and we see child like we're getting into an entirely different thing here now. But like it is just to say that I am consistent on this on both sides. I don't want, you know, anti natalist policies or pro natal. Well, I think I think the point you were going to make and didn't finish was that that.

KIMBERLY

Well, I think I think the point you were going to make and didn't finish was that that. It is about what the state that that population will eventually drop off and plateau, plateau. And we see that happening right now where South Korea, just like more people have a better standard of living and don't want to have as many children. And so, yes, their population numbers are declining. And that's because that's what steady state economy is really sort of about if it's just happens on its own. Right. And so I think that. That's an important point is that the role that states should provide is stability and security. And then whatever happens, but because of the backlash of fear, the fear of losing that nation of people, that ethnic group of people, then the government kicks in in the opposite direction. And so that's study state. The idea that we really want to just not push for more growth, but stabilize and try to rein in some of the consumption, overconsumption, hypercapitalism, rather than just growth, growth, growth based on GDP numbers. However, there are others who go even further than this, and they are the degrowth advocates. And décroissants was first used in 1972, at the same time, by an Austrian -French philosopher, André Gours, who was advocating for degrowth. And then... We see the next thing that comes along is in 1979 when the term degrowth actually came regularly into use. And then we see the resurgence of this again in 2002 that de croissants came to was in a symposium in France. That brought the attention back to degrowth because we were moving in this, right? We start to see a lot more attention drawn to the fact that we're not living in a sustainable way. We're overusing resources and borrowing into the future. So degrowth stresses the need for global North countries to scale back industrial production, industrial being the key word here, I think, and consumer material expectations, and argues that we can't continue on this current path because We are basically what's happening and they see is that in global North countries where people already have more than enough, the markets are pushing for selling more to people in saturated markets instead of actually refocusing on markets where they need to have more material goods to have a better standard of living. I mean, like how many varieties of Cheez -Its do we actually need? I know you love Oreos, but how many varieties of Oreos do we need?

JORDEN

No, so I think this is where we'll start getting into the I agree and disagree part, right? So I do agree that we've seen capitalism focus in on getting the next easiest dollar rather than pushing for a new market that might lead to $100. So I think that that's a fundamental problem with our market kind of drive right now and the incentives around that. So I agree with that. I also agree that, sure, we don't need the 15th kind of Oreo, right? But we do, you and I on the last episode. or I don't know when it came out. So it might've been the last of the second last. We went through a large list of companies though, that are creating new products that are sustainable. So we do want new ones on those. And this is where I get into the disagree because it really rapidly feels like to me, it's a moral, like it is, it is I'm being told morally what I should consume. And I think that as you know, and we've said on this show many, many times, I want to create and work towards a system where people can live their life sustainably and make the choices they want to make. And I don't. At least and, you know, this will get into it. Maybe it was my individualistic side coming out. But I don't want to be told that you should consume this because it is what you need. Well, OK, but what if I want to go for a road trip? I like I'm struggling with an example, but I think that's where it starts separating for me is I agree with the they've identified the correct problem that this is what's happening. And then it feels like it breaks down on the solution because in a lot of cases, it feels like a predetermined solution. Well, I think what you're actually describing is communism,

KIMBERLY

I think what you're actually describing is communism, right? Because that's basically, although to be accurate, what the Soviet Union was, was not communist. OK, that was not what Marx had in mind when he was talking about communism. But that's exactly what you're describing is like you get sugar. That's the sugar you get. And so you're talking about the same thing.

JORDEN

And I want to be careful and fair to degrowthers because I will not call it communism like directly. That is a different thing.

KIMBERLY

That is a different thing. Those are two actually different things. Yeah.

JORDEN

But I think that it does it does pull on a Marxist analysis. I think that like fundamentally it is a Marxist analysis of both capitalism and then the solutions to it. And I think like right now we'll talk about this, but we focus on the powerful in this current system and the problems they're having. And like when we talk. So like if we were if I was to suspend my problems with this and we had a council that could put this in globally, because that's the other thing here is would have to be global to work. Who decides and how do you not think that those elites who become the new powerful aren't going to make the same kind of in different ways? But like, yeah. And so while I will not call it communism, it is, in my opinion, a command and control system. It necessarily has to be.

KIMBERLY

it's a macro level system that has to be put in place. And the closest thing we've ever seen that almost resembles that, even though it's not exactly what communism was, is the Soviet experiment or the Chinese experiment. And so, so yeah, I mean, we talked about that. We also talked in terms of scaling back industrial production and consumer material expectations that also we talked about with planned obsolescence that again, a recent episode that why is it that For example, my electric toothbrush just died and I can't replace the battery in it. I have to replace the whole entire unit, which includes a completely functioning toothbrush and the charging station, which were all totally undamaged, but I can't change out the battery. That's planned obsolescence. That's making it so that I can't go in there and do that because it's easier and it's safer to target me because I can easily afford another electric toothbrush. And if I can't, I can certainly. afford a manual toothbrush with no problem. And so why not, right? Push that on to me. And so the degrowth advocates also say it's socially unjust to keep using these resources, especially in the global north. I think they would add on, I'm not that well -versed in like the, I haven't been into the weeds of the degrowth movement, but I would be willing to bet they would also argue that. And not just the fact that we use these resources, but the fact that we don't actually reuse, repair, recycle those resources as well. I mean, that's really part of it, that we're being socially unjust to the people in Global South who actually need these things. They could use those metals and those plastics or whatever to do other things. And so for them, it's that there's... more to life than just material goods. And because the people don't have sufficient material goods, their quality of life is being undermined.

JORDEN

A hundred percent. And I agree with that. Again, so perfect identification of the problem, right? But I think already there in your answer, you got to how, again, we don't have to do this through a degrowth model. In the last episode, we cited the tremendous economic opportunity from circular economy activities. Right. And how that's growing and how that will continue to grow. So and this is where it breaks down again for me. Right. It is like, OK, yes, we fully agree on the issue. OK, so now we're going to do this. And then they're like, no, no, no, we need to do this really heavy handed thing. I'm like, but so I'm fully supportive of more regulations. And this is where maybe like. I think the other thing to just state at the top, I think we have failed in the global north for allowing the regulatory system to be reduced to the point where capitalism can run amok. Like at the end of the day, capitalism to me is a system that has no limiting principles inherently. So you have to place them on the state for sorry, you have to place them from the state. Now, where I push back on capitalists, I'm using air quotes for everybody who can't see is they don't understand that you can't have capitalism without a state creating a market. You have only anarchy. Right. So this is like I fundamentally view the state as integral to capitalism because it creates the market and then sets the rules and they will do whatever is allowed within those rules. Right. So I think that's really where we have failed and where I would say like moving us towards. of these things is on the the actual regulatory side right that's really just neoliberal economic model is that's what after world war ii was an attempt to try to put those institutions those global institutions in place to have the regulations in place to rein in the ills of capitalism and that's exactly what the whole point of that was is to try to say okay we can't just let capitalism run amok instead

KIMBERLY

really just neoliberal economic model is that's what after world war ii was an attempt to try to put those institutions those global institutions in place to have the regulations in place to rein in the ills of capitalism and that's exactly what the whole point of that was is to try to say okay we can't just let capitalism run amok instead We need to cooperate and have rules about what we can do with the environment and pollution and resource usage and treatment of human beings and so forth. And and in the end, we see where we're at now, which is countries actually moving away from retracting from those those norms that were put into place. And so, yeah, I agree. And the funny thing is, is that. Of all my years of teaching, my students would ask me what my thoughts were. Oh, tell me your opinion. I'm not here to give you my opinion. I'm here just to talk about the information and give you the tools and the resources for critical thinking and deciding for yourself and then being able to use the information that you have to make a case for your argument. And so you keep saying we, we disagree on these things. And I'm wondering. If you are including me in this, because I don't feel like at this point I've actually told you like where I come down on this.

JORDEN

No, no. And even as I was preparing for this episode, I had I actually have a note in my notes of to not blame Kimberly or set us like like I'm when I'm saying we and for everybody. No, this is not Kimberly and I think this is I joked to Kimberly before the episode started of avoid saying anything on this publicly. for 10 years because i find that it is just becomes a fight and the people who are supportive of it it is it is a a moral question if you're either for this or i'm just as bad as everybody uh other capitalists so if i if i do fall into generalizations it's a little bit of a trigger response on my end so no i i just want to oh right apologize if you've gotten that oh no i just wanted to and that's the point is that that

KIMBERLY

oh no i just wanted to and that's the point is that that I also have a lot of issues with this, but it's important to understand what it's actually about. And that's what you started out the episode by saying is a lot of people aren't well informed in what it is that it's about. And I think that basically, as you pointed out, all of the principles, underlying principles are all things that we, you and I agree on in terms of like what's important. But it's about the implementation that's problematic. And that's the same problem that people had. And I don't want to hate to use Marx as the example, but with a lot of well, I will use Marx as an example because it's the only alternative we've seen to capitalism is command run economy. And so so that's something that we really almost have to use that as a comparison. But it's kind of almost unfair to do that because then. people end up conflating communism with degrowth and even maybe to the extent of steady state, which is definitely not in the same camp, even as degrowth. And so, and then to go on and make it even more confusing than this Japanese economist come there, actually the philosopher Kohai Saito comes along in 2020. And so think about the timeframe. This is COVID. And he wrote this book, Capitalism and the Anthropocene. And this got a lot of attention. And it sold like a half a million books in Japan, in just Japan alone. And so his whole premise was degrowth communism. And this was just like this philosopher who's trying to bring together the red of Marxism and the green of environmentalism. It has this huge mass white appeal in Japan, a country that to me is like... There's no way like they've had so many years of like unintentional degrowth. I can't even imagine that they would want to like, but they totally embraced this. And he just in 2023 followed up his ideas and slowed down. He's very much advocating degrowth communism. That is not what degrowth is about, though. The movement of degrowth is certainly not what steady state is about.

JORDEN

No, I think that's a really good point, too. And it's why I went with it. I use the word. I think it has a Marxist critique to it, a Marxist, because I think that that's the best way to separate out that it's not a communist. I mean, again, putting aside the new Japanese work, which I just want to say to everybody, I when I saw those stats on it, I said, OK, I guess I have to go read capitalism in the Anthropocene. And so but I and the reason I'm even. I get the hesitancy. I the word a communist is overused, right? That's communist. That's socialist is far too overused. But it also does bring people's a bunch of assumptions, opinions to it. And you can't have a discussion around the idea of degrowth. And two things are really one. I do think it is. similar to a marxist comparison in the sense that i often like personally i think marx got so much right on the problems of capitalism for certain i agree too yeah i think he had the same problem as degrowth which is that when you move to the next part of how do you fix it it breaks down right so i see parallels parallels there but i also i fundamentally believe and why i've engaged with this so much not just because it was an issue that kind of bugged me and i wanted to but the reason i've done so much reading on this is because If you can't find a good idea in something you disagree with, you're not trying hard enough and it says more about you. So I do think there is a lot here and it's a worthwhile topic for everybody, whether you're a full on capitalist, doesn't matter to whether you want to be sustainable hippie in the woods, right? Like I think that you both can take ideas from it and there are good critiques of your position that come from a degrowth frame. And that's what I think your point was.

KIMBERLY

that's what I think your point was. Well, that's okay. We've got that cleared up. I think that that's really important from what you said, just from the work that you do. If you want to do sustainability work, it's absolutely important to understand what people have in mind when they clump you in with degrowth and then just shut down. And so that's why I think it's important to be educated on these things, whether we agree with them or not. And so with degrowth, it's about this. desire to redefine what the good life is. And that's something that John Maynard Keynes was talking about, that he thought that with increased automation, that would free up people's time and then that would allow them to work less and then they would have more leisure time. But instead we see the exact crazy opposite happening where people are working more and more hours instead. And also we see this with happiness measures. We see happiness, oh, what country is the happiest country? Who are the happiest people? We see these numbers come out every single year. But they still take a backseat to how much money do people have, what attention, all of the attention that GDP growth gets.

JORDEN

Yeah. And this is what I want to do a plug here for an economist, Mark Analeski. His book, it's old now, like 2009, Happiness Economics. He's followed it up. But he actually created a measure and has worked with cities, including small towns in Alberta, Edmonton, and then has gone to the States afterwards, of creating a more holistic measure of economics that actually involves, it gets fuzzy because it actually involves survey work with the local community. And a big principle of it is that you actually can't measure a holistic vision of what is good economic growth without understanding the priorities of that community. Right. And so because one community might prioritize water more than than like, let's just say forestry. Right. So you get a different balance there. And I think that that is really interesting work and really something seminal for me that pushed me to think beyond like what is I think GDP. It's horrible because it's so flawed, but it's also so useful, which is why we can't get away from it. So anything we can add to that basket is really big for me.

KIMBERLY

Not having read that. It sounds a lot to me like what the World Bank was proposing with its Millennium Plan was to shift away from just focusing on GDP and instead focus on including human capital and natural capital,

KIMBERLY

to shift away from just focusing on GDP and instead focus on including human capital and natural capital, because without doing that, you don't get a balanced picture. And of course, the World Bank's got limited resources and a lot of people to help, but at the same time really need to have. include that they need to be able to do those local surveys. They need to be on the ground. They just lack the resources to be able to effectively do that.

JORDEN

But I think this also gets to a problem for me, again, going back to the broader kind of how do we implement either degrowth or steady stakes? I think the first step would be then. You're making invariably we think that we know, sorry, that GDP is a bad measure right now for capturing everything. Any sort of movement to a new measure will reduce complexity. Like that's what happens when we create measures. Right. And so. Part of me just thinks that when you play this out, unless you're doing it, you either have no measure of economics that works because you can't get everybody like, you know, every community all the way up to agree. Or again, we reach another imperfect measure. Now, I'm fine with that if we can get to a better state. But I think sometimes in these conversations, there's a little bit of utopianism that's brought into it, right? That if we get rid of the evils of GDP and we put in degrowth, and I'm not saying anyone here is saying this, but I think it's brought to the conversation a lot. that we will move to this perfect kind of state. And maybe I just have too much pessimism in me to think that we'll ever get to that.

KIMBERLY

So we've talked a lot about what degrowth is. How about what degrowth isn't, right? It's not communism, which I guess we kind of hammered on a lot. Steady state is certainly not capitalism. And it's not about... dissolving the state and communally owned property. In fact, it's very much about needing the state, as you mentioned earlier, about needing the state because the whole purpose, like the state, whether you look at it from promoting individual interests or promoting collective interests, it's still about providing that security umbrella. It's also about providing some sort of network across states in order for states to have interactions. And so we like to think that they're... All right, some of us, I mean, like to think that the international realm matters and that this is something that cooperation and coordination can very much help without, I hate the rise all boats analogy because it has failed us miserably. But at the same time, more people will be better off. More people have been better off because of capitalism for certain. Communism definitely was not, or the communist experiment was not. effective at all we saw exactly what happened to that and that it was not tenable and so you know are what do you think are we hopeful that steady state and degrowth will gain enough support to save the planet or is it even necessary like so now that you've sort of run down the pros and cons i suppose of both of them and the aspects of them that are worth pursuing and we've identified that the problem is in fact like how do you get from point a to point c because we disagree on b so what do you think yeah i just want to stop on the rising the boats one because i struggle with that too right because like empirically i know it's true because everybody on the planet now is living a better standard of life almost everybody yeah i should have my hand was doing it like yeah but yes we should be it should be careful

JORDEN

just want to stop on the rising the boats one because i struggle with that too right because like empirically i know it's true because everybody on the planet now is living a better standard of life almost everybody yeah i should have my hand was doing it like yeah

KIMBERLY

almost everybody yeah i

KIMBERLY

yeah but

JORDEN

yes we should be it should be careful The majority of the planet is living in better standards than they were even a few decades ago, but have not done enough. So you don't want to say it. The way I look at it is like that rising tide carried a few people a hundred couple feet up on the crest of the wave. And some people only got to sit in the puddle. That's how I mentally think about it to capture that.

KIMBERLY

I think that's an apt analogy.

JORDEN

Yeah. No, I do not have a lot of hope for degrowth as a so like I kind of wrote out a few things here in the hope of like, let's just pause and pull it down to one country. Right. Because I agree with you. You need more international cooperation to do this than we currently see. And listeners can go back to any episode on anything we've talked about that needs international cooperation. But I just I even try to think about this at a country level. Right. Like. Do we freeze GDP at current levels and say, so, OK, this is now frozen, right? But then we're locking in all of the inequality of the current system unless we're freezing it and doing massive redistribution so that now we're bringing up that puddle. We're trying to move it up and we're trying to bring that wave down. That gets into some thorny questions. Do you stop somebody from opening a new business because they might need new resources? It might be growth. But as I said, in my fuel example, what if it's the growth we want? And then now are we morally judging every individual business activity to say whether it works within our preferred growth? And then how do you allow innovation and change in a system that is especially more in steady state? I was thinking about this, that implies and is focused on maintaining a status quo. So I think when you start looking at it, even on a country level, it presents some really thorny questions that I don't think politically we could get the will to solve. But as I said at the start, I actually think that it's counterproductive to spend our time on those problems. We're spending our time on targeting areas in the current system where there's the biggest lever points for moving forward in sustainable development. And I think that it's definitely more of a personal approach than an empirical. I think I've highlighted why I think degrowth doesn't work from that side. But just personally, I feel like there are better ways that we can actually drive impact. So that's kind of why where I'm ending up on it.

KIMBERLY

Well, I think that you mentioned GDP as like the main thing again. And and as you know, I appreciate what you said earlier, which is. you need an actual measure. But GDP is just a made -up measure too. A lot of people might not know that that was just completely, it's made up and it can be manipulated as well, which is why we have the difference between GDP and GNI and other measurements and why it is that we use different measures in terms of whether we look at purchasing power parity or real. And so that's just also another number too. So I've got that issue with it. Also though, I wish we could just not focus on exclusively on that. I still think that GDP gets way too much emphasis. And I mean, in an already developed economy, how much more growth do you really need beyond sort of inflation anyway? And we see that, you know, countries are loaded for if they get up to like three or four target, if they could do that. Yes, when you see huge growth rates for India and China and other developing countries in the world, that's great because they need that. But for the United States or any other developed country, we definitely don't need that.

JORDEN

No, I think that's an amazing point. And I think you just hit it better than I've been saying it, which is because I keep talking about growth and I want these kinds of growth. None of that needs to be measured by purely GDP. And to your point, for a country like Canada or for America, where you are measuring out another percentage point of GDP. While there are benefits that come from that, I think that there's actually it's not the best way of even getting at that. And we could there are better measures and better ways of looking at all of the things that I've said I want this episode that aren't captured by GDP. So, yeah.

KIMBERLY

Well, I think, too, another point you had that was important is that it's about like income equality or redistribution. Right. Now, moving more toward toward more income equality would certainly solve some serious. sustainability issues but we know there's going to be a huge backlash for anybody who tries to readjust anything that that gives poor people money god forbid no so i actually think that this sorry just i think that this is a sign if you go back to the early 1900s 1910s

JORDEN

so i actually think that this sorry just i think that this is a sign if you go back to the early 1900s 1910s This is like when you start seeing socialism really start gaining traction, when you see communism start growing as more of a, and there were a lot at the time, you had like 50 different competing kind of ideas. And I, when I look at that historical period, I look at those as a response to the ills of the capitalism that we were seeing then, right? And I think that you see governments and you see industry more broadly kind of respond. We got the kids out of the mind. So, you know, we started putting in health requirements. The state stepped in in a big way. And I think that held off a lot of the actual switch that we would have seen if capitalism hadn't responded. So when I look at the kind of rise and degrowth or steady statism or alternative methods to capitalism. I almost see it as kind of like a rising feeling of this is broken again. And maybe not necessarily this solution is going to be the right one. But I do think that it's a moment where the system needs to respond and address these problems or it will see it break and we will get something else. Like I don't think you can stay in that tension period for too long.

KIMBERLY

Well, we try, we mostly fix them in global North countries. They have not been fixed in global South countries though. So we still see kids in mines and all of those other things that were adjusted for social safety nuts and so forth. And also, you know, the fact that following on that, we have two world wars and a great depression. So, so there's that too, right? That all of that was in response to the industrial revolution, what happened. And also along those lines of singing, two things. One, that we also saw the rise of socialist democracies, and they are some of the most well adjusted, most sustainably pushing in the sustainable direction. And so when we look at the Scandinavian countries and some others, that that's something that that has worked. But look at their history and how long it took them to get to that point. And also, there are also very homogenous societies as well, which helps. The other thing I was thinking about when you were talking about, again, about income redistribution is what's going to happen with AI. And now, especially as we move forward, I forget what the acronym is for guaranteed income. There's an acronym for that.

JORDEN

Oh, Universal UBI. I always forget that.

KIMBERLY

always forget that. But so giving everyone an income because basically they're not going to have a job. And so how are they going to spend money if they don't have a job? And so I think about this too.

JORDEN

Yeah, this is a weird one for me because I... I think we have a culture of overwork. And so I agree with, again, all that. But I actually think that we've gone almost in the critique, we've gone too far in devaluing the role of work in people's lives. So I think that I worry a lot about the income side of things, but I worry more about a world in which people don't have meaningful work to do. And what that'll actually lead to. And that scares me almost more like a world where it's just government paying out and you're you're told to sit at home. You don't contribute. That scares me because I do think that there is a very strong aspect of we're driving towards the world. My work contributes to a better world in this way. And I don't want to lose that, I guess. I agree because we already see that with more people in the United States anyway.

KIMBERLY

agree because we already see that with more people in the United States anyway. Younger people who are still living at home don't have meaningful jobs, don't have. ways to have meaning, you know, be meaningfully employed and contribute. And so I'm completely with you on that. So that's our episode on steady state and degrowth and degrowth communism, which are definitely two different things. If you haven't picked that up by now, if you enjoyed our episode of sustainable planet, or even if you didn't. Let us know, splanetpod at gmail .com. We're also on Facebook, LinkedIn, and YouTube. You'll find these links about our show and our show notes on splanetpod .com along with additional resources. You can read more on my Substack posts. We'd really appreciate it if you'd rate and review our Sustainable Planet episode on your podcast app. Thanks for listening and have a sustainable day.